|

From The Lincoln County News

April 21, 2004 Vol. 129 - No. 17

http://www.mainelincolncountynews.com/index.cfm?ID=6703

Whitefield Book Lover Fixes Leather Bound Friends

By Lucy L. Martin

Through restoration of 17th century books, Jon Robbins of Whitefield has met a lot of authors he never heard of as a college English major.

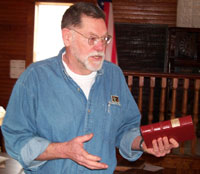

Speaking at the Whitefield Historical Society’s annual meeting Sunday in the Town House, the retired Wiscasset High School English teacher and Whitefield resident shared his love of old and rare books with low-key geniality, simultaneously offering a refresher course on tidbits of English history.

Robbins said he took up book repair after mending classroom paperbacks used by his students. When he retired about 10 years ago, he experimented on a 1937 reprint of a 19th century classic hardcover book by replacing its leather spine. He bought a used handbag at a Goodwill store and a bottle of Elmer’s glue.

“I was so pleased, I thought if I could do a spine, why not the whole cover?” It was the 1990s, animal rights advocates were getting regular play in the media, and all kinds of cast off leather goods were available. He bought a red leather raincoat for $5 and covered about 10 books. One of them was Dante’s Inferno translated by Longfellow. For a collection of essays by Carlyle, Robbins used a bomber jacket he found at Salvation Army.

His wife Judy’s decision to attend Harvard Divinity School drew Jon to Cambridge, where he met booksellers James and Devon Gray. Their specialty was books published before 1700. Jon was able to find 17th century books in Maine and purchased them from Maine dealers at a 20 percent discount, reselling them in Boston at a price that let him recoup his cost. Devon Gray, a bookbinder, “was amused” by Robbins’ efforts but scowled upon learning he used Elmer’s glue. “She taught me the Hippocratic oath of book dealers: ‘First, do no harm.’” She told him it was essential to use materials that would allow future mending, if needed.

When Robbins found a first edition of Milton, Devon informed him he was not going to use a Salvation Army jacket and he was going to mend the book using wheat paste, a proper adhesive made from flour and water.

In searching for old books he could buy at a price to make rebinding profitable, Robbins became a collector. As the Gray family grew (Devon had a baby who quickly graduated from a basket to toddlerhood, ranging freely around the book store), Robbins was asked to step in and do bookbinding for the couple. He now does about 10 books a year for the Grays and takes on projects for other dealers.

As a collector, Robbins said he likes to buy books that are damaged because he can afford them and also fix them. He buys leather by the hide from a California dealer who specializes in reins and cowboy chaps but also carries lighter weight stock.

Spines on old volumes disintegrate first, the former teacher said. Pollution from gaslights in earlier times was very damaging to books sitting on library shelves, making the spines crumble to dust.

An early purchase was a book offered by an English dealer over the Internet. When Robbins read the description “worm soiled, scuffed and torn”, he thought it would be a good challenge. The dealer e-mailed back that he would send the book postage paid “if you want to be so challenged.” It cost about $88 and was worth $1200. Robbins discovered an early edition of the book in the Colby College library and was able to photocopy a missing page, which was then reproduced on paper using a method that makes it look like the 17th century original.

One of the best aspects of old book restoration is “running into authors and events you’ve never heard of,” he said, citing Abraham Cooley whose books ran into 13 editions, and George Sandys, an English foreign service career officer whose 1626 translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses while Sandys served the colony of Virginia was hailed as “the first utterance” of literary spirit in colonial America.

Bookbinding also introduced Robbins to the prolific Jeremy Taylor, “the Shakespeare of English prose” and Church of England religious writer. “I’d never heard of him!” He also rebound a 1689 text on passive obedience, described on the title page as “non resistance of our lawful superiors”. Like most of his raptly attentive audience, Robbins had never heard of passive obedience and said he still wasn’t sure what it means, but discovering the text opened a door for him on a century he described as “rife with subjects writers wanted people to know about. It was an amazing century,” chronicling plagues, the fire of London, the revelations of Samuel Pepys’ diary, and the Restoration of the monarchy (1660) when Charles II took the throne after the Commonwealth period.

Robbins showed a variety of hefty leather books he has rescued, from a 1688 folio size Bible published in London to the oldest book he owns, a 1532 text on durable rag paper written by Savonarola, an Italian reformer and martyr who challenged the corrupt clergy of his time. The book is protected by a 19th century binding. “The paper is amazing,” Robbins said. “You’d think it was made yesterday.” At one time, he added, Egyptian mummies were imported into England so bookmakers could use the wrappings.

He also displayed facsimile pages from the Gutenberg Bible, the text that launched the printed book upon the world. Before the movable type printing press was invented c. 1450, books were made on vellum, derived from sheepskin, “one letter at a time by a monk in a scriptorium. Books were rare, expensive, and not widely read because most people were not readers,” Robbins observed.

China’s secrets of papermaking came to the West through Arabs, who had paper mills 800 years before the craft became established in England. By the 16th century, “it was possible to make books people could afford. Imagine how many sheep it takes to do a book if you’re using vellum, especially the large folio books,” Robbins said. He uses a calf sized piece of leather to do the binding on a large folio book.

The bookbinder also displayed an odd little volume with wooden boards covered in pigskin.

The son of a Unitarian minister whose family spent summers in Alna, Robbins grew up in Chicago and studied at Brown University in Providence. During his 31 years in education, he spearheaded a University of Maine program on curriculum coherence for teachers and has worked with Bowdoin College students interested in teaching. Robbins also developed and organized book groups for probationers in the corrections system.

Return |